The War Cloud Excerpt

1

0500 Hours

Offutt Air Force Base

Omaha, Nebraska

Every minute of every day since February 3, 1961, a Strategic Command “Looking Glass” plane carrying an Air Force general has been circling the Midwest, ready to seize control of America’s nuclear arsenal should a surprise attack destroy command posts on the ground. The program officially ended with the Cold War, but actually carries on under various guises and aircraft. Only once, in the skies of September 11, 2001, has a Looking Glass plane ever been spotted by the general public. Even then the Pentagon denied its existence.

This morning it was General Brad Marshall’s turn to play God.

Marshall gazed at the converted military Boeing 747-200 “Doomsday” jumbo jet waiting for him in the pre-dawn darkness as his black Chevy Suburban, wipers working furiously, braked to a halt and he stepped out.

The ice on the tarmac crunched under his brisk, powerful strides. The snow was coming down harder now. He turned up the collar of his overcoat and bore through the curtain of white to Looking Glass, its gigantic GE 80-series engines winding up to takeoff power. Originally, the plane was an EC-135C, then an E-6 Mercury. The new model, a modified E4-B conscripted from Operation Nightwatch, had triple the floor space and was practically a dead ringer for the president’s Air Force One. Only the small white dome on top betrayed its enhanced military capabilities.

So this is what Siberia feels like, Marshall thought, both of the bitter cold and his new obscure-if-critical posting. A “promotion to general” hatched by an insecure president to keep a war hero as far away as possible from TV crews.

At the base of the tall stairs leading up to the six-story-high plane stood an intelligence officer Marshall had never seen before, although he recognized him from a file somewhere.

The officer saluted as he approached. “General Marshall, sir.”

Marshall frowned. “What happened to Colonel Reynolds?”

“Flu, sir,” the intelligence officer explained eagerly. “I’m Colonel Quinn. I’ll be your second.”

Marshall looked Quinn over. He had handpicked the Looking Glass crew himself, and this ringer was second-string at best. The switch wasn’t entirely unexpected, but it annoyed Marshall that General Carver at Strategic Command hadn’t bothered to give him an official heads-up about such a critical assignment. It only confirmed just how routine and insignificant these flights had become to the Department of Defense.

“Try to keep up with me, Quinn,” Marshall said as he started up the steps.

Marshall worked his way through the main deck’s various compartments—a command work area, conference room, briefing room, an operations team work area, and a secondary communications compartment — and acknowledged the salutes and greetings of the admiring crew with a confident smile.

Inside the communications center, Major Tommie Banks lit up when Marshall entered, Quinn right behind.

“General Marshall, sir,” the curvy redhead said.

“Major Tom,” Marshall acknowledged. “Threat alert status?”

She handed him a report. “Orange, sir.”

Marshall looked over the report. “Flight forecast?”

She looked him in the eye. “Clear skies, sir.”

Marshall nodded. “The President. Give me his twenty.”

Major Tom said, “Back in Washington with everybody else for tonight’s State of the Union.”

“Not everybody,” Marshall said, handing back the report.

She nodded and said softly, “You deserve better, sir.”

“Don’t we all?” Marshall said and marched off.

Two armed Looking Glass officers were already waiting in the battle staff compartment when Marshall entered and sat down in his general’s swivel chair.

“Harney, Wilson.” Marshall nodded to the men. “Welcome to Air Armageddon. Please present your boarding passes.”

The young officers dutifully surrendered the nuclear authenticator codes they were carrying.

Marshall removed the key he wore around his neck and inserted it into one of two locks in the red steel box next to his seat. “Colonel Quinn?”

“Sir.” Quinn, who was hurrying in behind Marshall, produced his own key and inserted it into the second lock.

Marshall opened the double-padlocked safe.

“As you gentlemen know, a Looking Glass plane like ours is always in the air.” Marshall paused to look each officer in the eye. “In the event of surprise nuclear attack, we can command American forces from the air and launch our ICBMs by remote control. Colonel Quinn, as my second officer, you are watching me place the nuclear authenticator codes in here for safekeeping.”

Marshall placed the code cards that Harney and Wilson had given him inside the safe, next to the two launch keys that together could unleash the Apocalypse. He locked the double padlocks with the safe keys. He hung the long chain of his key to the safe around his neck again. He then pocketed Quinn’s second key.

“God forbid we’ll ever need these.”

Marshall turned his attention to a pre-flight checklist. Wilson and Harney stood like statues on either side of him, emotionless. But he could feel Quinn’s stare.

Quinn cleared his throat. “Sir.”

“Yes,” Marshall said without looking up. But he could hear the uncertainty in Quinn’s voice.

“The other key, sir.”

Marshall played it cool. “What about it, Quinn?”

“Regulations state that both keys are not to be in the possession of a single officer,” Quinn said, sounding forced.

Marshall knew that this kind of situation could throw even the most seasoned officer, and Quinn was hardly that. “I know the regulations,” Marshall replied evenly. “I think we have too many regulations these days, don’t you?”

At that moment Major Tom appeared. “General Marshall,” she said, “the tower has cleared us for takeoff.”

Marshall handed her his checklist and locked eyes with Quinn. “Who’s our pilot today, Quinn?”

Quinn did his best not to look at his clipboard. It took a few seconds, but he got it right. “That would be Captain Delaney, sir. And Rogers is co-pilot.”

Marshall nodded. “Trained them myself. Just like the rest of the crew. Everybody but you, Quinn. We don’t just look out for each other. We’ve made a pact. You know the kind of loyalty I’m talking about, Quinn?”

Quinn said nothing. His eyes were wide, his lips pressed tightly.

“I didn’t think so.” Marshall turned to his crew and smiled. “To your stations, officers.”

Wilson and Harney did as they were told. As did Major Tom.

Marshall heard Quinn unlock his sidearm holster, and when he looked up again he saw the barrel of Quinn’s .38 mm pistol pointed at him.

Quinn said, “Sir, I’m going to have to ask you for that key.”

Marshall smiled. His voice turned softer. “You’re new to Looking Glass, aren’t you?”

“My first flight, sir. But I’ve flown several times with Colonel Kozlowski aboard the Nightwatch plane.”

“Flying with the chauffeur of the president’s Air Force limo isn’t the same as flying with me, Colonel. So, if you don’t mind, I’m going to keep your key.”

“Regulations, sir,” said Quinn as his hand holding the pistol trembled slightly.

“I thought you were a team player, Quinn.”

“I am, sir. But I insist you surrender the key, or I’ll be forced to shoot you.”

“Go ahead, Quinn. Make my day.”

Quinn looked bewildered. But he took a firmer grasp of his pistol. “On the count of three, sir. Three…”

Marshall stared a hole through him and said nothing.

“Two…”

Quinn’s voice started to shake again. But Marshall had to admit to himself that the kid could stand his ground.

“One…”

Marshall’s face broke into a wide grin.

“Congratulations, Colonel.” Marshall removed the second key from his pocket and dangled it in front of Quinn. “You passed the test.”

Quinn grabbed the key with one hand and with his other holstered the sidearm and wiped his forehead. “For a minute there, sir, I thought…”

“Yeah, I know,” Marshall said. “You thought I was flipping out. Next time pull the trigger.”

“Yes, sir, “ Quinn said. “I will, sir.”

Marshall tapped his armrest commlink and said, “Captain Delaney.”

The pilot’s voice came through on the speaker. “Yes, sir.”

“Let’s roll.”

The engines roared to takeoff speed as the Looking Glass plane began to barrel down the runway. A minute later they lifted off the ground and soared into dark skies. At last, thought Marshall, the National Airborne Military Command Post was in the clouds where she—and he—belonged.

2

0730 Hours

O Street

Washington, D.C.

The headline in the Washington Post read “No Sachs Education for Kids.” A photo showed a beleaguered U.S. Secretary of Education Deborah Sachs at a meeting of the nation’s governors in Washington. Her deer-in-the-headlights look said it all.

Sachs frowned at the picture of herself. It was above a smaller story about a slain Metro security guard whose body was found in a rail yard. She adjusted the phone to her ear as she sipped her morning coffee while the TV blared.

“The President is expected to announce the resignation of his outspoken and controversial Secretary of Education after tonight’s State of the Union address,” Matt Lauer was saying on the Today show, and proceeded to recite her most recent run-ins with the Administration. Then Lauer said, “Moving on to the crisis in the Far East…”

She lowered the volume as her friend Lauren at Commerce took the call and immediately offered her condolences.

“No, he hasn’t given me my resignation yet,” Sachs said, flicking her freshly cut black hair from under her chin, which pinned the phone to her shoulder. She was going to grow it out, she decided, now that she no longer required the Beltway cut of a Cabinet secretary. “I have to give it to him this morning. Then he’ll accept it tomorrow. Tonight is all about him, remember? All I know is that Nadine has been a super assistant.”

Blah, blah, blah. Lauren was such a spin doctor with the excuses.

“Well, could you see what you could do for her just the same? Thanks.”

Sachs hung up and stared out the windows at the falling snow. Her Georgetown row house until now had been her sole refuge from the nonsense of Washington. The hunter green walls, white trim and oils over the fireplace had offered an illusion of security and tradition in her otherwise uncertain life.

But it couldn’t shield her from urban Democrats who made a federal case for public education while their own children attended private schools. Or from suburban Republicans whose children enjoyed quality public schools and who demanded vouchers for private schools. Or from the nagging reality she had no home to go back to again because Richard was gone forever, and without him it just wouldn’t be home. But in the process she was depriving Jennifer.

She was mulling over this last painful thought when her assistant Nadine emerged from the front hallway, immaculate in her latest fashionable suit beyond her pay grade, ready to tackle lobbyists, teachers unions and Congress. Her dark hair was slicked back. She smiled broadly, keeping up a good front.

“Morning, boss.”

“For some Americans,” Sachs replied.

“Told you being a public servant isn’t worth the cost after two years,” Nadine said, and then stopped. “What’s this?” She was pointing to the packed overnight carry-on by the door.

“I’m grabbing the shuttle to see Jennifer,” Sachs said. “You book my ticket like I asked?”

“Uh, no,” Nadine said. “You’re going to see the President and tell him why you should keep your job.”

Nadine walked over to the desk and picked up what looked like a student term paper awash in red corrections. In the upper right hand corner was a big, fat “B.”

“And what’s this, Madame Secretary?”

Sachs said, “My speech for Jennifer’s school assembly.”

“You graded yourself?”

“I’ll do better on the next draft,” Sachs replied without a trace of embarrassment.

“Next draft?” Nadine looked at her Rolex. Sachs had told her to stop with the bling as they were trying to help inner city schools, but it was no use. “Hey, we canceled that speech. You have a meeting at the White House this morning. Why are we still talking?”

“I rescheduled,” Sachs told her. “I’m not going to disappoint Jennifer again. Besides, the President is going to cancel on me anyway. He always does. This time permanently. Just text him my resignation.”

Sachs grabbed her carry-on and rolled it behind her down the hallway and out the front door into the wintry day and the waiting government limousine, leaving Nadine to lock up after her. The driver popped the trunk and dropped her bag inside, then opened the rear door for her to get inside where it was warm.

Nadine finished a call at the curb, then climbed in and shut the door, incredulous. “Only you, boss,” she said as the limo pulled into the street.

“Meaning what?” Sachs asked her.

“Meaning here you are losing your job on national TV and all you can do is worry about your assistant’s ass and some speech nobody’s going to hear.”

“Jennifer and her friends are going to hear it,” Sachs said. “You have a better suggestion?”

“Lecture circuit,” Nadine replied.

Sachs laughed. “If nobody listened to me when I was Secretary of Education, why would they listen to me afterward? Besides, the whole silver lining is that my New York-Washington commuting days are over. I can spend more time with Jennifer.”

Nadine grimaced. “She’s what, ten? Give her a year and she’ll want you out of her life for good.”

“Thank you, Nadine, that’s comforting,” Sachs said. “She’s thirteen and needs me more than ever. Two years is a long time for a girl to live with her aunt. She hates me. If I’m going to be living in New York again, I’m going to be living with my daughter.”

Nadine said, “We’ll work something out. Now let’s go see the President. Maybe he’s changed his mind.”

Sachs was firm. “Look, did you book me on the shuttle to New York or not?”

Nadine flashed the email confirmation on her government-issued BlackBerry. “I’ve got you out of Reagan National in forty minutes.”

“Nadine, I don’t know what I’m going to do without you.”

“You go to New York and we’re both gonna find out,” Nadine warned her. “Because if you don’t make it back tonight for the State of the Union, you’re gonna piss off the president.”

“That’s my job, remember?”

“Was your job,” Nadine huffed.

Sachs smiled. “I’ve got a better one now.”

3

1000 Hours

Hay-Adams Hotel

USAF Colonel Joseph Kozlowski woke up and shifted under the huge down comforter that covered the king-size bed. He reached to feel for Sherry, but she was gone, without so much as leaving a warm spot.

Kozlowski turned onto his back and blinked his eyes open. He could hear the hair dryer in the bathroom. He held up his watch and squinted. Then he slipped out of bed and plodded toward the curtains and pulled them back. The bleak January light seeped in as he looked across H Street at the White House. The snow was still coming down, burying the Rose Garden and Ellipse. He could barely make out the towering spike of the Washington Monument beyond.

He smelled coffee and saw that Sherry had room service bring up breakfast for one. All that was left was some picked-over fruit and a pile of newspapers screaming about yet another crisis in the Far East. He fished out a melon cube with his fingers and poured himself some lukewarm coffee.

He was halfway through his cup when Sherry emerged from the bathroom with her blow-dried blonde hair draped over her terrycloth robe with the Hay-Adams Hotel logo on it, which she left open just enough to remind him why he never turned her down for these hotel hideaways.

Kozlowski said, “Leaving so soon?”

“Got to finish Vanderhall’s reaction to the State of the Union address,” she said, sliding open the closet door to reveal her Armani suit next to his uniform. The same uniform he had been wearing for eight years now, still a colonel.

“So where am I going, Sherry?”

“You’re going nowhere, Koz.”

Kozlowski watched her dress. “You finally figured that out?”

“The snow, silly.” Sherry helped herself to his Purple Heart medal from his uniform.

“What are you doing?”

“The colors go with my jacket,” she said as she pinned it beneath the lapel of her blazer.

“You ever been wounded while serving your country?” Kozlowski asked her. “That’s what it means.”

“I won’t lose it.” She put on her gold earrings and spoke to him from the closet mirror. “It’s not like it’s actually worth anything. Stolen honor is legal now.”

No, thought Kozlowski, just a couple of lives. But it was no use arguing with Sherry. She was 27 and wouldn’t understand, he concluded as he watched her grab her Gucci soft leather briefcase and walk out the door, off to more important things like personal advancement.

Kozlowski walked over to the open closet and looked at his blue uniform where the missing medal belonged. Sherry was right. It was just clothing, bland at that, with some cheap ribbons and medals.

Cheap like his bosses. Cheap like the promises they made and the company they kept.

Everything he grew up to believe in—the armed forces, the presidency, even the United States—no longer seemed mythic, but quaint and kindergarten. There were no rules anymore. The current occupant of the White House was yet another empty suit, and he wondered if America was even capable of producing a leader worth following into battle anymore.

He unbuckled the holster sitting on the closet shelf and removed his sidearm, a .38 standard-issue automatic pistol. He felt its weight in his hand.

Almost ten years of his life had passed in two overseas wars, he realized. Just like that. What could I have been by now? A general like Brad Marshall? Certainly a father if Mary hadn’t left him. They could have had three or four kids by now. He could be skiing or having snowball fights in Colorado instead of sitting here, feeling old, used-up, worthless.

He pointed the gun to his head and put his finger on the trigger.

4

1144 Hours

The White House

U.S. President Peter Rhinehart paced beneath George Washington on the wall of the Oval Office. He had fifteen minutes before his final meeting with Deborah Sachs, and he still needed to work on his delivery of his State of the Union address.

“And let us not live in the past,” he recited, stressing the word “past” like it was bad. “But look forward to the future.”

Meaning his own political future, he thought, when the ivory desk phone rang. The LED display flashed: Chairman, JCS. Line Secure. Top Secret. It was General Robert Sherman, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, calling from the Pentagon.

Annoyed, Rhinehart picked up. “What is it, Bob?”

“Mr. President, we have a situation.”

Rhinehart’s morning intelligence briefing had spelled out a number of situations, so he could only guess.

“The SS-20?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m about to address the American people, dammit, and our friend General Marshall is breathing down my neck in the polls,” the President huffed. “I don’t have time for any false–”

“Mr. President, NEST teams have confirmed there is a stolen Soviet SS-20 nuclear warhead somewhere in Washington. Now the Russians say they have evidence that the Chinese planted it, and that it is set to detonate in five minutes.”

“Five minutes?” Rhinehart frowned. “What do the Chinese have to say?”

“The Chinese say that if anybody’s planted a nuke in Washington, it’s the Russians or Islamic State proxies.”

“Goddammit,” groaned Rhinehart. “Every major elected official in America has got to be in Washington. How imminent is the threat?”

As if on cue, a military aide burst through the door carrying a black briefcase — the “football” containing nuclear authorization codes. Rhinehart stared at the attaché, speechless.

“I’ll brief you after you’re secure in the bunker,” Sherman pleaded with him on the phone. “Mr. President, we have no time.”

Rhinehart hung up and walked out of the Oval Office, the football and military aide close behind. He brushed past the White House military operator at the switchboard on the way out.

“The vice president just arrived,” the operator reported.

“Tell him he’s leaving,” Rhinehart replied. “Get my chopper to airlift him to Andrews.”

“Yes, Mr. President.”

“Call Jack and Stan and have them meet me downstairs,” the President continued. “Alert conference.”

“Situation Room?”

“No. The bunker.”

The military operator hit a button on his communications console, sounding an alarm.

5

1145 Hours

The Westchester School

Bedford, New York

The Westchester School in Bedford, New York, was a public charter school, one of America’s finest. Sachs sent Jennifer here because she didn’t want to compromise herself as a champion of public education by enrolling her daughter in a private school. But at the time she couldn’t find an acceptable public school in Washington. So Aunt Dina and the Westchester Middle School seemed to be the answer, even if Jennifer called all public schools, local or charter, “government schools.” Only now, Sachs wondered if she had sacrificed her relationship with her daughter on the altar of her idealism.

The verdict was waiting for her inside. A sullen Jennifer, arms folded across her chest, sat in the office of Principal Mel Boyle. The school clock said 11:44, a few minutes faster than her own watch, so Sachs was running eight minutes late. Eight minutes of hell from the look on Jennifer’s face.

“So why aren’t you in Washington, putting other children first?” Jennifer asked without looking up.

“Shhh,” Sachs replied with a smile. “Mom’s playing hooky.”

Principal Melanie Boyle, a Barbie blonde in slacks and heels, walked in. “Nice to see you again, Madame Secretary.”

“Principal Boyle,” Sachs said, greeting her.

“Doctor Boyle,” the principal corrected her. “Everybody’s gathering in the gymnasium. We so appreciate your visit, although I wish it were under better circumstances.”

Sachs didn’t know if Boyle meant her impending job execution or if she was referring to Jennifer. “Is there a problem?”

Boyle slid a file across her desk. Sachs could see the big fat “F” circled in red. “This is Jennifer’s U.S. Constitution final,” Boyle explained. “Not only could she not name all of the current members of the president’s Cabinet, she couldn’t even name one. Not even the Secretary of Education.”

Boyle raised a perfectly waxed eyebrow.

Sachs studied the exam for a minute and then put it down.

“Well, I’d probably miss that one, too, if the answer wasn’t me,” she said. “But you know all the rest, Jennifer. What’s going on?”

“Globalization,” Jennifer said with all seriousness. “The U.S. Constitution is obsolete. To quote Socrates, I’m not a New Yorker or an American, but a citizen of the world.”

If Principal Boyle weren’t as serious as Jennifer, Sachs would have burst out laughing. But she kept a straight face and addressed her daughter. “Maybe, darling. But most of the world’s democracies have constitutions based on ours. And unless you want to live in a police state, and condemn the rest of humanity to the same fate, you’d better learn which way is up.”

“What planet are you from, Mom?” Jennifer made a dramatic, sweeping gesture with her hand, the back of which still bore an admission stamp from some event. “Look around you. Have you seen this government school? This IS a police state. My Bill of Rights didn’t keep the government from sucking in your tax dollars, nor Ms. Boyle from opening my private locker and going through my diary, or kicking me out of the school dance last Friday.”

“School dance?” Sachs repeated, looking at Jennifer. “You never told me about a dance. Did you go with—”

“She was wearing thong underwear,” Boyle declared, cutting her off. “Highly visible underwear, I might add.”

Sachs stared at her 13-year-old daughter, trying to process this ambush of zingers from Boyle. “You were wearing a thong?”

“Well, duh.” Jennifer was non-apologetic. “Everybody at the dance could see my thong after Ms. Vice Squad here lifted up my skirt.”

Sachs stared at Boyle. “You looked under my daughter’s skirt?”

“Whatever,” said Jennifer. “Can we get going already?”

“We should move along,” Boyle helpfully agreed, clearly looking to delay the inevitable, ugly parent-teacher conference with Sachs. “Everybody’s in the gymnasium.”

Sachs looked at both of them, not sure whom she was more furious at. “Fine,” she said. “Let’s not keep them waiting. I’ll deal with you later, ladies. Both of you.”

Are you loving The War Cloud?

She was the last link in America’s chain of command.

Now she’s the world’s last hope.

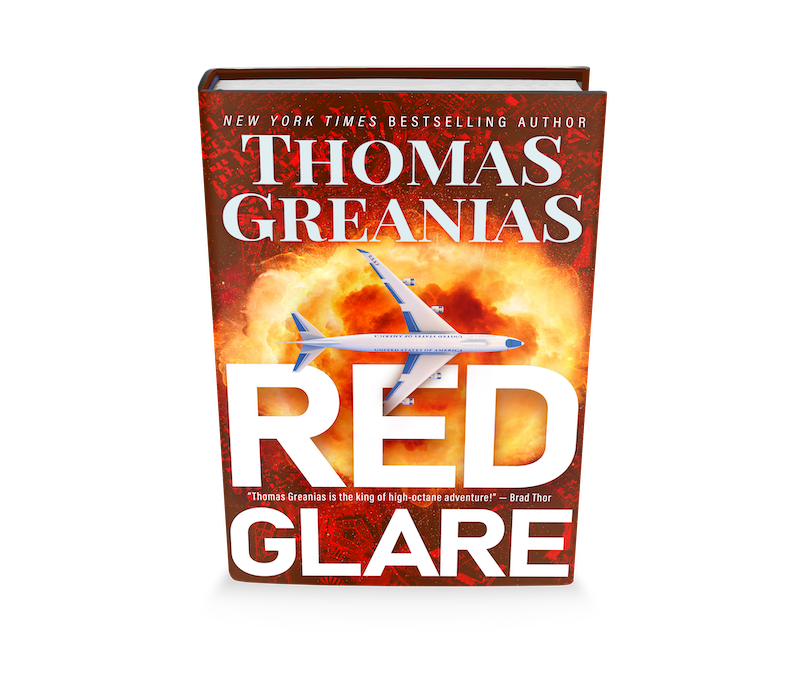

Brad Marshall was a brilliant Air Force general and popular war hero. Too popular for his own good. The president has reassigned his potential rival to the shadows: command of a doomsday plane that officially doesn’t exist, flying endless circles over nuclear missiles in the heartland that nobody at the Pentagon believes will ever be launched.

Then a catastrophic attack on Washington destroys the Pentagon and kills the President and the next fifteen Cabinet members in the line of succession. Now Marshall, who wrote the military’s Doomsday playbook, holds the keys to America’s nuclear arsenal. And he’s ready to unleash it to avenge his country.

Only one person stands in his way: Deborah Sachs, the Secretary of Education. On the day she was to be fired, she is now the accidental “designated survivor” and acting President. She has ultimate nuclear authorization—and a mind of her own.

Reviews of Red Glare

A top-flight thriller.

— Blogcritics.org

Extremely fast-paced. An exciting adventure.

— Booklist

Thomas Greanias is the KING of HIGH-OCTANE adventure.

— Brad Thor, Act of War

Thomas Greanias is a superb writer who knows how to tell a tale with style and substance.

— Nelson Demille, The General’s Daughter

The War Cloud Excerpt

1

0500 Hours

Offutt Air Force Base

Omaha, Nebraska

Every minute of every day since February 3, 1961, a Strategic Command “Looking Glass” plane carrying an Air Force general has been circling the Midwest, ready to seize control of America’s nuclear arsenal should a surprise attack destroy command posts on the ground. The program officially ended with the Cold War, but actually carries on under various guises and aircraft. Only once, in the skies of September 11, 2001, has a Looking Glass plane ever been spotted by the general public. Even then the Pentagon denied its existence.

This morning it was General Brad Marshall’s turn to play God.

Marshall gazed at the converted military Boeing 747-200 “Doomsday” jumbo jet waiting for him in the pre-dawn darkness as his black Chevy Suburban, wipers working furiously, braked to a halt and he stepped out.

The ice on the tarmac crunched under his brisk, powerful strides. The snow was coming down harder now. He turned up the collar of his overcoat and bore through the curtain of white to Looking Glass, its gigantic GE 80-series engines winding up to takeoff power. Originally, the plane was an EC-135C, then an E-6 Mercury. The new model, a modified E4-B conscripted from Operation Nightwatch, had triple the floor space and was practically a dead ringer for the president’s Air Force One. Only the small white dome on top betrayed its enhanced military capabilities.

So this is what Siberia feels like, Marshall thought, both of the bitter cold and his new obscure-if-critical posting. A “promotion to general” hatched by an insecure president to keep a war hero as far away as possible from TV crews.

At the base of the tall stairs leading up to the six-story-high plane stood an intelligence officer Marshall had never seen before, although he recognized him from a file somewhere.

The officer saluted as he approached. “General Marshall, sir.”

Marshall frowned. “What happened to Colonel Reynolds?”

“Flu, sir,” the intelligence officer explained eagerly. “I’m Colonel Quinn. I’ll be your second.”

Marshall looked Quinn over. He had handpicked the Looking Glass crew himself, and this ringer was second-string at best. The switch wasn’t entirely unexpected, but it annoyed Marshall that General Carver at Strategic Command hadn’t bothered to give him an official heads-up about such a critical assignment. It only confirmed just how routine and insignificant these flights had become to the Department of Defense.

“Try to keep up with me, Quinn,” Marshall said as he started up the steps.

Marshall worked his way through the main deck’s various compartments—a command work area, conference room, briefing room, an operations team work area, and a secondary communications compartment — and acknowledged the salutes and greetings of the admiring crew with a confident smile.

Inside the communications center, Major Tommie Banks lit up when Marshall entered, Quinn right behind.

“General Marshall, sir,” the curvy redhead said.

“Major Tom,” Marshall acknowledged. “Threat alert status?”

She handed him a report. “Orange, sir.”

Marshall looked over the report. “Flight forecast?”

She looked him in the eye. “Clear skies, sir.”

Marshall nodded. “The President. Give me his twenty.”

Major Tom said, “Back in Washington with everybody else for tonight’s State of the Union.”

“Not everybody,” Marshall said, handing back the report.

She nodded and said softly, “You deserve better, sir.”

“Don’t we all?” Marshall said and marched off.

Two armed Looking Glass officers were already waiting in the battle staff compartment when Marshall entered and sat down in his general’s swivel chair.

“Harney, Wilson.” Marshall nodded to the men. “Welcome to Air Armageddon. Please present your boarding passes.”

The young officers dutifully surrendered the nuclear authenticator codes they were carrying.

Marshall removed the key he wore around his neck and inserted it into one of two locks in the red steel box next to his seat. “Colonel Quinn?”

“Sir.” Quinn, who was hurrying in behind Marshall, produced his own key and inserted it into the second lock.

Marshall opened the double-padlocked safe.

“As you gentlemen know, a Looking Glass plane like ours is always in the air.” Marshall paused to look each officer in the eye. “In the event of surprise nuclear attack, we can command American forces from the air and launch our ICBMs by remote control. Colonel Quinn, as my second officer, you are watching me place the nuclear authenticator codes in here for safekeeping.”

Marshall placed the code cards that Harney and Wilson had given him inside the safe, next to the two launch keys that together could unleash the Apocalypse. He locked the double padlocks with the safe keys. He hung the long chain of his key to the safe around his neck again. He then pocketed Quinn’s second key.

“God forbid we’ll ever need these.”

Marshall turned his attention to a pre-flight checklist. Wilson and Harney stood like statues on either side of him, emotionless. But he could feel Quinn’s stare.

Quinn cleared his throat. “Sir.”

“Yes,” Marshall said without looking up. But he could hear the uncertainty in Quinn’s voice.

“The other key, sir.”

Marshall played it cool. “What about it, Quinn?”

“Regulations state that both keys are not to be in the possession of a single officer,” Quinn said, sounding forced.

Marshall knew that this kind of situation could throw even the most seasoned officer, and Quinn was hardly that. “I know the regulations,” Marshall replied evenly. “I think we have too many regulations these days, don’t you?”

At that moment Major Tom appeared. “General Marshall,” she said, “the tower has cleared us for takeoff.”

Marshall handed her his checklist and locked eyes with Quinn. “Who’s our pilot today, Quinn?”

Quinn did his best not to look at his clipboard. It took a few seconds, but he got it right. “That would be Captain Delaney, sir. And Rogers is co-pilot.”

Marshall nodded. “Trained them myself. Just like the rest of the crew. Everybody but you, Quinn. We don’t just look out for each other. We’ve made a pact. You know the kind of loyalty I’m talking about, Quinn?”

Quinn said nothing. His eyes were wide, his lips pressed tightly.

“I didn’t think so.” Marshall turned to his crew and smiled. “To your stations, officers.”

Wilson and Harney did as they were told. As did Major Tom.

Marshall heard Quinn unlock his sidearm holster, and when he looked up again he saw the barrel of Quinn’s .38 mm pistol pointed at him.

Quinn said, “Sir, I’m going to have to ask you for that key.”

Marshall smiled. His voice turned softer. “You’re new to Looking Glass, aren’t you?”

“My first flight, sir. But I’ve flown several times with Colonel Kozlowski aboard the Nightwatch plane.”

“Flying with the chauffeur of the president’s Air Force limo isn’t the same as flying with me, Colonel. So, if you don’t mind, I’m going to keep your key.”

“Regulations, sir,” said Quinn as his hand holding the pistol trembled slightly.

“I thought you were a team player, Quinn.”

“I am, sir. But I insist you surrender the key, or I’ll be forced to shoot you.”

“Go ahead, Quinn. Make my day.”

Quinn looked bewildered. But he took a firmer grasp of his pistol. “On the count of three, sir. Three…”

Marshall stared a hole through him and said nothing.

“Two…”

Quinn’s voice started to shake again. But Marshall had to admit to himself that the kid could stand his ground.

“One…”

Marshall’s face broke into a wide grin.

“Congratulations, Colonel.” Marshall removed the second key from his pocket and dangled it in front of Quinn. “You passed the test.”

Quinn grabbed the key with one hand and with his other holstered the sidearm and wiped his forehead. “For a minute there, sir, I thought…”

“Yeah, I know,” Marshall said. “You thought I was flipping out. Next time pull the trigger.”

“Yes, sir, “ Quinn said. “I will, sir.”

Marshall tapped his armrest commlink and said, “Captain Delaney.”

The pilot’s voice came through on the speaker. “Yes, sir.”

“Let’s roll.”

The engines roared to takeoff speed as the Looking Glass plane began to barrel down the runway. A minute later they lifted off the ground and soared into dark skies. At last, thought Marshall, the National Airborne Military Command Post was in the clouds where she—and he—belonged.

2

0730 Hours

O Street

Washington, D.C.

The headline in the Washington Post read “No Sachs Education for Kids.” A photo showed a beleaguered U.S. Secretary of Education Deborah Sachs at a meeting of the nation’s governors in Washington. Her deer-in-the-headlights look said it all.

Sachs frowned at the picture of herself. It was above a smaller story about a slain Metro security guard whose body was found in a rail yard. She adjusted the phone to her ear as she sipped her morning coffee while the TV blared.

“The President is expected to announce the resignation of his outspoken and controversial Secretary of Education after tonight’s State of the Union address,” Matt Lauer was saying on the Today show, and proceeded to recite her most recent run-ins with the Administration. Then Lauer said, “Moving on to the crisis in the Far East…”

She lowered the volume as her friend Lauren at Commerce took the call and immediately offered her condolences.

“No, he hasn’t given me my resignation yet,” Sachs said, flicking her freshly cut black hair from under her chin, which pinned the phone to her shoulder. She was going to grow it out, she decided, now that she no longer required the Beltway cut of a Cabinet secretary. “I have to give it to him this morning. Then he’ll accept it tomorrow. Tonight is all about him, remember? All I know is that Nadine has been a super assistant.”

Blah, blah, blah. Lauren was such a spin doctor with the excuses.

“Well, could you see what you could do for her just the same? Thanks.”

Sachs hung up and stared out the windows at the falling snow. Her Georgetown row house until now had been her sole refuge from the nonsense of Washington. The hunter green walls, white trim and oils over the fireplace had offered an illusion of security and tradition in her otherwise uncertain life.

But it couldn’t shield her from urban Democrats who made a federal case for public education while their own children attended private schools. Or from suburban Republicans whose children enjoyed quality public schools and who demanded vouchers for private schools. Or from the nagging reality she had no home to go back to again because Richard was gone forever, and without him it just wouldn’t be home. But in the process she was depriving Jennifer.

She was mulling over this last painful thought when her assistant Nadine emerged from the front hallway, immaculate in her latest fashionable suit beyond her pay grade, ready to tackle lobbyists, teachers unions and Congress. Her dark hair was slicked back. She smiled broadly, keeping up a good front.

“Morning, boss.”

“For some Americans,” Sachs replied.

“Told you being a public servant isn’t worth the cost after two years,” Nadine said, and then stopped. “What’s this?” She was pointing to the packed overnight carry-on by the door.

“I’m grabbing the shuttle to see Jennifer,” Sachs said. “You book my ticket like I asked?”

“Uh, no,” Nadine said. “You’re going to see the President and tell him why you should keep your job.”

Nadine walked over to the desk and picked up what looked like a student term paper awash in red corrections. In the upper right hand corner was a big, fat “B.”

“And what’s this, Madame Secretary?”

Sachs said, “My speech for Jennifer’s school assembly.”

“You graded yourself?”

“I’ll do better on the next draft,” Sachs replied without a trace of embarrassment.

“Next draft?” Nadine looked at her Rolex. Sachs had told her to stop with the bling as they were trying to help inner city schools, but it was no use. “Hey, we canceled that speech. You have a meeting at the White House this morning. Why are we still talking?”

“I rescheduled,” Sachs told her. “I’m not going to disappoint Jennifer again. Besides, the President is going to cancel on me anyway. He always does. This time permanently. Just text him my resignation.”

Sachs grabbed her carry-on and rolled it behind her down the hallway and out the front door into the wintry day and the waiting government limousine, leaving Nadine to lock up after her. The driver popped the trunk and dropped her bag inside, then opened the rear door for her to get inside where it was warm.

Nadine finished a call at the curb, then climbed in and shut the door, incredulous. “Only you, boss,” she said as the limo pulled into the street.

“Meaning what?” Sachs asked her.

“Meaning here you are losing your job on national TV and all you can do is worry about your assistant’s ass and some speech nobody’s going to hear.”

“Jennifer and her friends are going to hear it,” Sachs said. “You have a better suggestion?”

“Lecture circuit,” Nadine replied.

Sachs laughed. “If nobody listened to me when I was Secretary of Education, why would they listen to me afterward? Besides, the whole silver lining is that my New York-Washington commuting days are over. I can spend more time with Jennifer.”

Nadine grimaced. “She’s what, ten? Give her a year and she’ll want you out of her life for good.”

“Thank you, Nadine, that’s comforting,” Sachs said. “She’s thirteen and needs me more than ever. Two years is a long time for a girl to live with her aunt. She hates me. If I’m going to be living in New York again, I’m going to be living with my daughter.”

Nadine said, “We’ll work something out. Now let’s go see the President. Maybe he’s changed his mind.”

Sachs was firm. “Look, did you book me on the shuttle to New York or not?”

Nadine flashed the email confirmation on her government-issued BlackBerry. “I’ve got you out of Reagan National in forty minutes.”

“Nadine, I don’t know what I’m going to do without you.”

“You go to New York and we’re both gonna find out,” Nadine warned her. “Because if you don’t make it back tonight for the State of the Union, you’re gonna piss off the president.”

“That’s my job, remember?”

“Was your job,” Nadine huffed.

Sachs smiled. “I’ve got a better one now.”

3

1000 Hours

Hay-Adams Hotel

USAF Colonel Joseph Kozlowski woke up and shifted under the huge down comforter that covered the king-size bed. He reached to feel for Sherry, but she was gone, without so much as leaving a warm spot.

Kozlowski turned onto his back and blinked his eyes open. He could hear the hair dryer in the bathroom. He held up his watch and squinted. Then he slipped out of bed and plodded toward the curtains and pulled them back. The bleak January light seeped in as he looked across H Street at the White House. The snow was still coming down, burying the Rose Garden and Ellipse. He could barely make out the towering spike of the Washington Monument beyond.

He smelled coffee and saw that Sherry had room service bring up breakfast for one. All that was left was some picked-over fruit and a pile of newspapers screaming about yet another crisis in the Far East. He fished out a melon cube with his fingers and poured himself some lukewarm coffee.

He was halfway through his cup when Sherry emerged from the bathroom with her blow-dried blonde hair draped over her terrycloth robe with the Hay-Adams Hotel logo on it, which she left open just enough to remind him why he never turned her down for these hotel hideaways.

Kozlowski said, “Leaving so soon?”

“Got to finish Vanderhall’s reaction to the State of the Union address,” she said, sliding open the closet door to reveal her Armani suit next to his uniform. The same uniform he had been wearing for eight years now, still a colonel.

“So where am I going, Sherry?”

“You’re going nowhere, Koz.”

Kozlowski watched her dress. “You finally figured that out?”

“The snow, silly.” Sherry helped herself to his Purple Heart medal from his uniform.

“What are you doing?”

“The colors go with my jacket,” she said as she pinned it beneath the lapel of her blazer.

“You ever been wounded while serving your country?” Kozlowski asked her. “That’s what it means.”

“I won’t lose it.” She put on her gold earrings and spoke to him from the closet mirror. “It’s not like it’s actually worth anything. Stolen honor is legal now.”

No, thought Kozlowski, just a couple of lives. But it was no use arguing with Sherry. She was 27 and wouldn’t understand, he concluded as he watched her grab her Gucci soft leather briefcase and walk out the door, off to more important things like personal advancement.

Kozlowski walked over to the open closet and looked at his blue uniform where the missing medal belonged. Sherry was right. It was just clothing, bland at that, with some cheap ribbons and medals.

Cheap like his bosses. Cheap like the promises they made and the company they kept.

Everything he grew up to believe in—the armed forces, the presidency, even the United States—no longer seemed mythic, but quaint and kindergarten. There were no rules anymore. The current occupant of the White House was yet another empty suit, and he wondered if America was even capable of producing a leader worth following into battle anymore.

He unbuckled the holster sitting on the closet shelf and removed his sidearm, a .38 standard-issue automatic pistol. He felt its weight in his hand.

Almost ten years of his life had passed in two overseas wars, he realized. Just like that. What could I have been by now? A general like Brad Marshall? Certainly a father if Mary hadn’t left him. They could have had three or four kids by now. He could be skiing or having snowball fights in Colorado instead of sitting here, feeling old, used-up, worthless.

He pointed the gun to his head and put his finger on the trigger.

4

1144 Hours

The White House

U.S. President Peter Rhinehart paced beneath George Washington on the wall of the Oval Office. He had fifteen minutes before his final meeting with Deborah Sachs, and he still needed to work on his delivery of his State of the Union address.

“And let us not live in the past,” he recited, stressing the word “past” like it was bad. “But look forward to the future.”

Meaning his own political future, he thought, when the ivory desk phone rang. The LED display flashed: Chairman, JCS. Line Secure. Top Secret. It was General Robert Sherman, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, calling from the Pentagon.

Annoyed, Rhinehart picked up. “What is it, Bob?”

“Mr. President, we have a situation.”

Rhinehart’s morning intelligence briefing had spelled out a number of situations, so he could only guess.

“The SS-20?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m about to address the American people, dammit, and our friend General Marshall is breathing down my neck in the polls,” the President huffed. “I don’t have time for any false–”

“Mr. President, NEST teams have confirmed there is a stolen Soviet SS-20 nuclear warhead somewhere in Washington. Now the Russians say they have evidence that the Chinese planted it, and that it is set to detonate in five minutes.”

“Five minutes?” Rhinehart frowned. “What do the Chinese have to say?”

“The Chinese say that if anybody’s planted a nuke in Washington, it’s the Russians or Islamic State proxies.”

“Goddammit,” groaned Rhinehart. “Every major elected official in America has got to be in Washington. How imminent is the threat?”

As if on cue, a military aide burst through the door carrying a black briefcase — the “football” containing nuclear authorization codes. Rhinehart stared at the attaché, speechless.

“I’ll brief you after you’re secure in the bunker,” Sherman pleaded with him on the phone. “Mr. President, we have no time.”

Rhinehart hung up and walked out of the Oval Office, the football and military aide close behind. He brushed past the White House military operator at the switchboard on the way out.

“The vice president just arrived,” the operator reported.

“Tell him he’s leaving,” Rhinehart replied. “Get my chopper to airlift him to Andrews.”

“Yes, Mr. President.”

“Call Jack and Stan and have them meet me downstairs,” the President continued. “Alert conference.”

“Situation Room?”

“No. The bunker.”

The military operator hit a button on his communications console, sounding an alarm.

5

1145 Hours

The Westchester School

Bedford, New York

The Westchester School in Bedford, New York, was a public charter school, one of America’s finest. Sachs sent Jennifer here because she didn’t want to compromise herself as a champion of public education by enrolling her daughter in a private school. But at the time she couldn’t find an acceptable public school in Washington. So Aunt Dina and the Westchester Middle School seemed to be the answer, even if Jennifer called all public schools, local or charter, “government schools.” Only now, Sachs wondered if she had sacrificed her relationship with her daughter on the altar of her idealism.

The verdict was waiting for her inside. A sullen Jennifer, arms folded across her chest, sat in the office of Principal Mel Boyle. The school clock said 11:44, a few minutes faster than her own watch, so Sachs was running eight minutes late. Eight minutes of hell from the look on Jennifer’s face.

“So why aren’t you in Washington, putting other children first?” Jennifer asked without looking up.

“Shhh,” Sachs replied with a smile. “Mom’s playing hooky.”

Principal Melanie Boyle, a Barbie blonde in slacks and heels, walked in. “Nice to see you again, Madame Secretary.”

“Principal Boyle,” Sachs said, greeting her.

“Doctor Boyle,” the principal corrected her. “Everybody’s gathering in the gymnasium. We so appreciate your visit, although I wish it were under better circumstances.”

Sachs didn’t know if Boyle meant her impending job execution or if she was referring to Jennifer. “Is there a problem?”

Boyle slid a file across her desk. Sachs could see the big fat “F” circled in red. “This is Jennifer’s U.S. Constitution final,” Boyle explained. “Not only could she not name all of the current members of the president’s Cabinet, she couldn’t even name one. Not even the Secretary of Education.”

Boyle raised a perfectly waxed eyebrow.

Sachs studied the exam for a minute and then put it down.

“Well, I’d probably miss that one, too, if the answer wasn’t me,” she said. “But you know all the rest, Jennifer. What’s going on?”

“Globalization,” Jennifer said with all seriousness. “The U.S. Constitution is obsolete. To quote Socrates, I’m not a New Yorker or an American, but a citizen of the world.”

If Principal Boyle weren’t as serious as Jennifer, Sachs would have burst out laughing. But she kept a straight face and addressed her daughter. “Maybe, darling. But most of the world’s democracies have constitutions based on ours. And unless you want to live in a police state, and condemn the rest of humanity to the same fate, you’d better learn which way is up.”

“What planet are you from, Mom?” Jennifer made a dramatic, sweeping gesture with her hand, the back of which still bore an admission stamp from some event. “Look around you. Have you seen this government school? This IS a police state. My Bill of Rights didn’t keep the government from sucking in your tax dollars, nor Ms. Boyle from opening my private locker and going through my diary, or kicking me out of the school dance last Friday.”

“School dance?” Sachs repeated, looking at Jennifer. “You never told me about a dance. Did you go with—”

“She was wearing thong underwear,” Boyle declared, cutting her off. “Highly visible underwear, I might add.”

Sachs stared at her 13-year-old daughter, trying to process this ambush of zingers from Boyle. “You were wearing a thong?”

“Well, duh.” Jennifer was non-apologetic. “Everybody at the dance could see my thong after Ms. Vice Squad here lifted up my skirt.”

Sachs stared at Boyle. “You looked under my daughter’s skirt?”

“Whatever,” said Jennifer. “Can we get going already?”

“We should move along,” Boyle helpfully agreed, clearly looking to delay the inevitable, ugly parent-teacher conference with Sachs. “Everybody’s in the gymnasium.”

Sachs looked at both of them, not sure whom she was more furious at. “Fine,” she said. “Let’s not keep them waiting. I’ll deal with you later, ladies. Both of you.”

Are you loving The War Cloud?

About Thomas

Thomas Greanias is a New York Times bestselling novelist and one of the world’s leading authors of adventure. His books in print have been translated into multiple languages and sold in 200 nations around the globe. A former journalist and on-air correspondent for NBC, Greanias infuses his international thrillers with provocative issues ripped from tomorrow’s headlines. Follow Thomas Greanias on Facebook, Google+ and Twitter. Subscribe to his official newsletter to go behind the scenes and get the latest on his next blockbuster.